| SPARC (Osteonectin) ELISA Kit, Antibody, Recombinant | |

| Associated with Diabetes Complications,Cardiovascular Disease and Tumors | |

| Search for SPARC Products and order it online please visiting www.aviscerabioscience.com | |

Alternative name:

|

|

|

|

|

Human SPARC ELISA Kit SK00766-06 was used by Dr. Lee SH on following paper |

|

Associations among SPARC mRNA expression in adipose tissue, serum SPARC concentration and metabolicparameters in Korean women |

|

Objective: Secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) is expressed in most tissues and is also secreted by adipocytes. The associations of SPARC mRNA expression in visceral adipose tissue (VAT), subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue (SAT), serum SPARC concentration, and metabolic parameters in Korean women are investigated. |

|

| Lee SH et al. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013 Nov;21(11):2296-302. doi: 10.1002/oby.20183. Epub 2013 May 13. | |

Human SPARC ELISA Kit SK00766-06 was used by Dr. Lee YJ on following paer. |

|

Serum SPARC and matrix metalloproteinase-2 and metalloproteinase-9 concentrations after bariatric surgery inobese adults |

|

| Background Remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM) of adipose tissue is regarded as part of the pathophysiology of obesity. Secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) was the first ECM protein described in adipose tissue. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) also play a role in ECM remodeling, and MMP-2 and MMP-9 may be associated with abnormal ECM metabolism. Here, we investigated changes in serum SPARC, MMP-2, and MMP-9 concentrations after bariatric surgery in obese adults. Methods We recruited 34 obese patients who were scheduled to undergo bariatric surgery for weight loss. We analyzed changes in serum SPARC, MMP-2, and MMP-9 concentrations before and 9 months after bariatric surgery and any associations between changes in SPARC, MMP-2, and MMP-9 concentrations and obesity-related parameters. Results Serum leptin levels significantly decreased, and the serum adiponectin level significantly increased after bariatric surgery. The serum SPARC concentration decreased significantly from 165.0 ± 18.2 to 68.7 ± 6.7 ng/mL (p< 0.001), and the MMP-2 concentration also decreased significantly from 262.2 ± 15.2 to 235.9 ± 10.5 ng/mL (p< 0.001). Changes in the serum SPARC concentration were significantly correlated with HOMA-IR changes, and changes in the serum MMP-9 concentration were found to inversely correlate with serum adiponectin changes. Conclusion These findings show that significant decreases in serum SPARC and MMP-2 concentrations occur after bariatric surgery. Our results thus suggest that weight loss via bariatric surgery could alter the ECM environment, and that these changes are related to certain metabolic changes. | |

| Lee YJ et al. Obes Surg. 2014 Apr;24(4):604-10. | |

A novel myokine, secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC), suppresses colon tumorigenesis via regular exercise |

|

| OBJECTIVE: Several epidemiological studies have shown that regular exercise can prevent the onset of colon cancer, although the underlying mechanism is unclear. Myokines are secreted skeletal muscle proteins responsible for some exercise-induced health benefits including metabolic improvement and anti-inflammatory effects in organs. The purpose of this study was to identify new myokines that contribute to the prevention of colon tumorigenesis. METHODS: To identify novel secreted muscle-derived proteins, DNA microarrays were used to compare the transcriptome of muscle tissue in sedentary and exercised young and old mice. The level of circulating secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) was measured in mice and humans that performed a single bout of exercise. The effect of SPARC on colon tumorigenesis was examined using SPARC-null mice. The secretion and function of SPARC was examined in culture experiments. RESULTS: A single bout of exercise increased the expression and secretion of SPARC in skeletal muscle in both mice and humans. In addition, in an azoxymethane-induced colon cancer mouse model, regular low-intensity exercise significantly reduced the formation of aberrant crypt foci in wild-type mice but not in SPARC-null mice. Furthermore, regular exercise enhanced apoptosis in colon mucosal cells and increased the cleaved forms of caspase-3 and caspase-8 in wild-type mice but not in SPARC-null mice. Culture experiments showed that SPARC secretion from myocytes was induced by cyclic stretch and inhibited proliferation with apoptotic effect of colon cancer cells. CONCLUSIONS: These findings suggest that exercise stimulates SPARC secretion from muscle tissues and that SPARC inhibits colon tumorigenesis by increasing apoptosis. |

|

| Aoi W, et al.Gut. 2012 Aug 9. [Epub ahead of print] | |

|

|

|

| Secreted protein, acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC), a matricellular protein, modulates extracellular matrix assembly and turnover in many physiological processes. SPARC-null mice exhibit an increased accumulation of adipose tissue. To distinguish between the functions of SPARC in adipogenesis during development and adulthood, we studied wild-type (WT) and SPARC-null mice maintained on a normal (low-fat) or high-fat (HF) diet. On an HF diet, SPARC-null mice exhibited significantly greater weight gain, in comparison to their WT counterparts, and had an enhanced cortical bone area that was likely due to increased mechanical loading. Diet-induced obesity (DIO) was also associated with an increase in vertebral trabecular bone in WT mice, but a significant change in this parameter was not observed in SPARC-null animals. We show that SPARC inhibits mitotic clonal expansion of preadipocytes at an early stage of adipogenesis. Moreover, there were substantially diminished levels of type I collagen in SPARC-null adipose tissue, as well as a reduction in the number of cross-linked, mature collagen fibers. In the absence of SPARC, mice show enhanced DIO. In adult animals, SPARC functions in the production and remodeling of adipose tissue, as well as in the regulation of preadipocyte differentiation. | |

| Nie J., et al. Connect Tissue Res. 2011 Apr;52(2):99-108. Epub 2010 Jul 8. | |

| SPARC: a key player in the pathologies associated with obesity and diabetes. | |

| SPARC (secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine, also known as osteonectin or BM-40) is a widely expressed profibrotic protein with pleiotropic roles, which have been studied in a variety of conditions. Notably, SPARC is linked to human obesity; SPARC derived from adipose tissue is associated with insulin resistance and secretion of SPARC by adipose tissue is increased by insulin and the adipokine leptin. Furthermore, SPARC is associated with diabetes complications such as diabetic retinopathy and nephropathy, conditions that are ameliorated in the Sparc-knockout mouse model. As a regulator of the extracellular matrix, SPARC also contributes to adipose-tissue fibrosis. Evidence suggests that adipose tissue becomes increasingly fibrotic in obesity. Fibrosis of subcutaneous adipose tissue may restrict accumulation of triglycerides in this type of tissue. These triglycerides are, therefore, diverted and deposited as ectopic lipids in other tissues such as the liver or as intramyocellular lipids in skeletal muscle, which predisposes to insulin resistance. Hence, SPARC may represent a novel and important link between obesity and diabetes mellitus. This Review is focused on whether SPARC could be a key player in the pathology of obesity and its related metabolic complications. | |

| Kos K, Wilding JP.Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2010 Apr;6(4):225-35. Epub 2010 Mar 2. | |

| Cardiac extracellular matrix remodeling: fibrillar collagens and Secreted Protein Acidic and Rich in Cysteine (SPARC) | |

| The cardiac interstitium is a unique and adaptable extracellular matrix (ECM) that provides a milieu in which myocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells communicate and function. The composition of the ECM in the heart includes structural proteins such as fibrillar collagens and matricellular proteins that modulate cell:ECM interaction. Secreted Protein Acidic and Rich in Cysteine (SPARC), a collagen-binding matricellular protein, serves a key role in collagen assembly into the ECM. Recent results demonstrated increased cardiac rupture, dysfunction and mortality in SPARC-null mice in response to myocardial infarction that was associated with a decreased capacity to generate organized, mature collagen fibers. In response to pressure overload induced-hypertrophy, the decrease in insoluble collagen incorporation in the left ventricle of SPARC-null hearts was coincident with diminished ventricular stiffness in comparison to WT mice with pressure overload. This review will focus on the role of SPARC in the regulation of interstitial collagen during cardiac remodeling following myocardial infarction and pressure overload with a discussion of potential cellular mechanisms that control SPARC-dependent collagen assembly in the heart. | |

| McCurdy S, et al. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010 Mar;48(3):544-9. Epub 2009 Jul 3. | |

| Proteins involved in platelet signaling are differentially regulated in acute coronary syndrome: a proteomic study | |

BACKGROUND: Platelets play a fundamental role in pathological events underlying acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Because platelets do not have a nucleus, proteomics constitutes an optimal approach to follow platelet molecular events associated with the onset of the acute episode. |

|

Fernández Parguiña A, et al. PLoS One. 2010 Oct 14;5(10):e13404. |

|

| Identification of Adipocyte Genes Regulated by Caloric Intake | |

Context: Changes in energy intake have marked and rapid effects on metabolic functions, and some of these effects may be due to changes in adipocyte gene expression that precede alterations in body weight. Objective: The aim of the study was to identify adipocyte genes regulated by changes in caloric intake independent of alterations in body weight. Research Design and Methods: Obese subjects given a very low-caloric diet followed by gradual reintroduction of ordinary food and healthy subjects subjected to overfeeding were investigated. Adipose tissue biopsies were taken at multiple time-points, and gene expression was measured by DNA microarray. Genes regulated in the obese subjects undergoing caloric restriction followed by refeeding were identified using two-way ANOVA corrected with Bonferroni. From these, genes regulated by caloric restriction and oppositely during the weight-stable refeeding phase were identified in the obese subjects. The genes that were also regulated, in the same direction as the refeeding phase, in the healthy subjects after overfeeding were defined as being regulated by caloric intake. Results were confirmed using real-time PCR or immunoassay. Results: Using a significance level of P < 0.05 for all comparisons, 52 genes were down-regulated, and 50 were up-regulated by caloric restriction and regulated in the opposite direction by refeeding and overfeeding. Among these were genes involved in lipogenesis (ACLY, ACACA, FASN, SCD), control of protein synthesis (4EBP1, 4EBP2), |

|

| Niclas Franck et al. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism , doi:10.1210/jc.2009-2534. published online onNovember 3, 2010 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

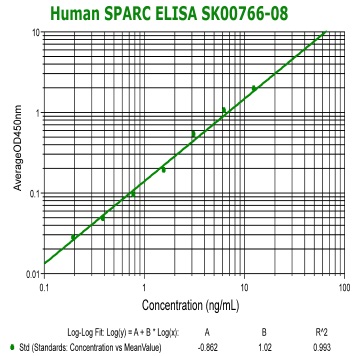

Human SPARC(Osteonectin) ELISA Code No.: SK00766-08 Size: 96 T Price: $460.00 USD Standard Range:0.19-12.5 ng/ml Sensitivity:0.10 ng/ml Specificity: Human SPARC Calibration: recombinant human SPARC (HEK293 derived) Sample Type: serum Dilution Factor: 40 IntraCV: 6-8% InterCV: 10-12% Protocol: PDF |

|

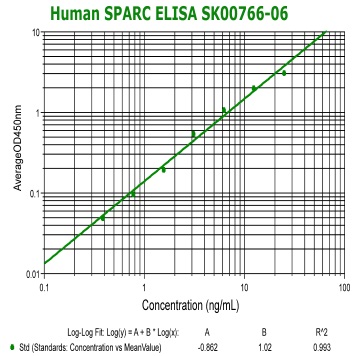

Human SPARC(Osteonectin) ELISA Code No.: SK00766-06 Size: 96 T Price: $420.00 USD Standard Range:0.39-25 ng/ml Sensitivity:0.15 ng/ml Specificity: Human SPARC Calibration: recombinant human SPARC (HEK293 derived) Sample Type: serum Dilution Factor: 40 IntraCV: 6-8% InterCV: 10-12% Protocol: PDF |

|

Rat/MousePARC(Osteonectin) ELISA Code No.: SK00766-02 Size: 96 T Price: $420.00 USD Standard Range:0.128-2000 ng/ml Dynamic Range: 0.64- 2000 ng/ml Sensitivity:0.128 ng/ml Sample Type: serum, EDTA plasma Sample requres: 120 ul, 50 ul per well Dilution Factor: 2~4 (Optimal dilutions should be determined by each laboratory for each application) IntraCV: 4-6% InterCV: 8-10% Protocol: PDF |

|

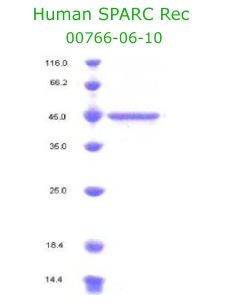

Human

Osteonectin/SPARC Recombinant Code No.: 00766-06-10 Size: 10 ug Price: $250.00 USD Protein ID:P09486 Gene ID: 6678 MW:45 KD Tag: His Tag on C-Terminus Expressed: 293 cells Purity: 95% Data Sheet: PDF |

|

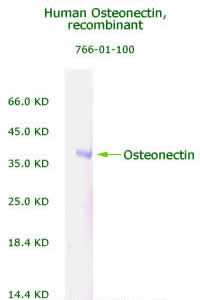

Human

Osteonectin/SPARC Recombinant Code No.: 00766-01-100 Size: 100 ug Price: $240.00 USD Protein ID:P09486 Gene ID: 6678 MW:36 KD Tag: His Tag on N-Terminus Expressed: E. Coli Purity: 95% Data Sheet: PDF |

|

Rat

Osteonectin/SPARC Recombinant Code No.: 00766-03-100 Size: 100 ug Price: $360.00 USD Protein ID:P16975 Gene ID: 24791 MW:50 KD Tag: His Tag on N-Terminus Expressed: E. Coli Purity: 95% Data Sheet: PDF |

| Mouse

Osteonectin/SPARC Recombinant Code No.: 00766-07-10 Size: 10 ug Price: $100.00 USD Protein ID:NP_033268 Gene ID: NM_009242 MW:45 KD Tag: His Tag on C-Terminus Expressed: 293 cells Purity: 95% Data Sheet: PDF |

|

|

Anti Human

Osteonectin/SPARC IgG Code No.: A00766-01-100 Size: 100 ug Price: $220.00 USD Host: Rabbit Antigen: human SPARC Rec. Ab Type: Polyclonal IgG Purification: Protein A Applications: E, IHC Working Dilution: 2 ug/ml) Data Sheet: PDF |

|

Anti Human

Osteonectin/SPARC IgG Code No.: A00766-01-100 Size: 100 ug Price: $220.00 USD Host: Rabbit Antigen: human SPARC Rec. Ab Type: Polyclonal IgG Purification: Protein A Applications: E, IHC Working Dilution: 2 ug/ml) Data Sheet: PDF |

|

Anti Human

Osteonectin/SPARC IgG Code No.: A00766-01-100 Size: 100 ug Price: $220.00 USD Host: Rabbit Antigen: human SPARC Rec. Ab Type: Polyclonal IgG Purification: Protein A Applications: E, IHC Working Dilution: 2 ug/ml) Data Sheet: PDF |

|

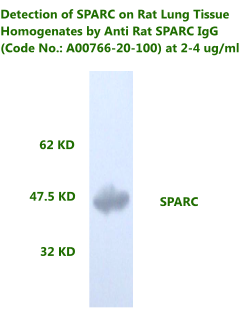

Anti Rat

Osteonectin/SPARC IgG Code No.: A00766-20-100 Size: 100 ug Price: $300.00 USD Host: Rabbit Antigen: rat SPARC Rec. Ab Type: Polyclonal IgG Purification: Protein A Applications: WB,E, IHC Working Dilution: WB (0.25-0.5 ug/ml) Data Sheet: PDF |

|

Anti Rat

Osteonectin/SPARC IgG Code No.: A00766-20-100 Size: 100 ug Price: $300.00 USD Host: Rabbit Antigen: rat SPARC Rec. Ab Type: Polyclonal IgG Purification: Protein A Applications: WB,E, IHC Working Dilution: WB (0.25-0.5 ug/ml) Data Sheet: PDF |

|

Anti

Osteonectin/SPARC IgG Code No.: A00766-20-100 Size: 100 ug Price: $300.00 USD Host: Rabbit Antigen: rat SPARC Rec. Specificity: human, rat, Mouse Ab Type: Polyclonal IgG Purification: Protein A Applications: WB,E, IHC Working Dilution: WB (0.25 ug/ml) Data Sheet: PDF |

|

|

| Name | Code No. |

Size |

Price ($) |

| SPARC / Osteonectin (Human) ELISA Kit | 96 T |

460.00 |

|

| SPARC / Osteonectin (Human) ELISA Kit | 96 T |

420.00 |

|

| Rat/Mouse SPARC ELISA Kit | SK00766-02 | 96 T | 420.00 |

| SPARC/Osteonectin (Human) Rec. | 00766-01-50 |

50 ug |

150.00 |

| SPARC/Osteonectin (Human) Rec. | 100 ug |

240.00 |

|

| SPARC/Osteonectin (Human) Rec. | 00766-01-1000 |

1000 ug |

1400.00 |

| SPARC/Oosteonectin (Human),293 cell derived | 10 ug |

250.00 |

|

| SPARC/Osteonectin (Rat), Rec. | 00766-03-100 | 100 ug | 360.00 |

| Anti SPARC/Osteonectin (Human) IgG | 100 ug |

220.00 |

|

| Anti SPARC/Osteonectin (Human) IgG , Cy3 conjugated | A00766-01-50C3 |

50 ug |

395.00 |

| Anti SPARC/Osteonectin (Human) IgG , Cy5 conjugated | A00766-01-50C5 |

50 ug |

395.00 |

| Anti SPARC/Osteonectin (Human) IgG , FAM conjugated | A00766-01-50F |

50 ug |

360.00 |

| Anti SPARC/Osteonectin (Human) IgG , Rhodamine B conjugated | A00766-01-50RH |

50 ug |

360.00 |

| Anti SPARC/Osteonectin (Human) IgG , Biotinylated conjugated | 50 ug |

360.00 |

|

| Anti SPARC/Osteonectin (Human) Monoclonal Antibody | 100 ug |

360.00 |

|

| Anti SPARC/Osteonectin (Human) Monoclonal Antibody | 100 ug |

300.00 |

|

| Anti SPARC/Osteonectin (Human) Monoclonal IgG, Biotinylated | A00766-04-50B |

50 ug |

395.00 |

| Anti SPARC/Osteonectin (Human) Monoclonal IgG, Cy3 conjugated | A00766-04-50C3 |

50 ug |

460.00 |

| Anti SPARC/Osteonectin (Human) Monoclona lAntibody | 100 ug |

300.00 |

|

| Anti SPARC/Osteonectin (Human) Monoclonal Antibody | 100 ug |

300.00 |

|

| Anti SPARC/Osteonectin (Human) Monoclonal Antibody | 100 ug |

300.00 |

|

| Anti SPARC/Osteonectin (Human) Monoclonal Antibody | 100 ug |

300.00 |

|

| Anti SPARC/Osteonectin (Human) Monoclonal Antibody | 100 ug |

300.00 |

|

| Anti SPARC/Osteonectin (Human) Monoclonal Antibody | 100 ug |

300.00 |

|

| Anti Rat SPARC/Osteonectin IgG | A00766-20-100 | 100 ug | 300.00 |

| Anti SPARC/Osteonectin (Rat) Monoclonal Antibody | 100 ug |

300.00 |

|

| Anti SPARC/Osteonectin (Rat) Monoclonal Antibody | 100 ug |

300.00 |

| References |

1: Nie J,et al. Inactivation of SPARC enhances high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice. Connect Tissue Res. 2010 Jul 8. [Epub ahead of print] |